Assessing Chronic Fatigue with the Cortisol Awakening Response

Allison Smith, ND

Assessing Chronic Fatigue with the Cortisol Awakening Response

by Allison Smith, ND

The cortisol awakening response (CAR) blazed an important trail for adrenal research starting in the late 90s as a unique index of chronic stress’s impact on cortisol and chronic disease. In the last 10 years as the industry has shed the outdated terminology of adrenal fatigue, the CAR graduated from clinical research into the commercial laboratory space which made it available to doctors and patients. And when it’s collected correctly, it can be a game changer, providing a clear and accurate picture of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis function that a diurnal cortisol pattern alone can only hint at.

The CAR may as well have been discovered to assist in identifying the root cause of a very common primary care complaint—chronic fatigue. To understand how, let’s review the physiology of the CAR and discuss how the treatment approach to chronic fatigue can be tailored based on the CAR.

The Purpose of the CAR and its Physiology

The CAR takes place upon waking even in the absence of stressful situations or any sort of danger. Strictly speaking, it’s not a stress response. It’s actually evidence of communication between body and brain that exists to move a person from conscious and awake, to a state of alertness. In fact, that early-morning cortisol rise in response to waking ends sleep inertia, lowers inflammation, assists with glucose balance, and engages the immune surveillance system .

You can liken the whole process to the action of a slingshot. Through the night, the drop in cortisol, the rise in melatonin in the darkness of the night (that takes you deep into slow-wave sleep and hippocampal oscillation) slowly pulls back, extending and tightening the band of the slingshot—with cortisol in the cockpit.

In the immediate time before you open your eyes, the pituitary begins ramping up adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) pulsing based on central body clocks. Those pulses of ACTH do conceivably reach the adrenals, but the cortisol-producing tissue of the adrenals isn’t fully stimulated until the eyes open and light enters the retina.

Light stimulates the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) as well as the hippocampus and with that stimulation comes a separate, direct stimulatory potential to the adrenal gland from the brain. This light stimulation from brain to adrenal and lifting of inhibition by a healthy hippocampus releases the flood gates and the adrenals begin to respond to ACTH with a burst of cortisol production—and the slingshot is released.

Cortisol soars by at least 50% in the first 30 minutes after opening the eyes and then it gradually declines through the day in a diurnal fashion. This is the way you functionally assess HPA axis sensitivity without a formal ACTH stimulation test. Importantly, the CAR has been associated with myriad disease states that arise from chronic stress etiologies. The CAR can be easily assessed before and monitored after treatment is applied to determine whether or not stress resilience has improved.

Elevated CAR

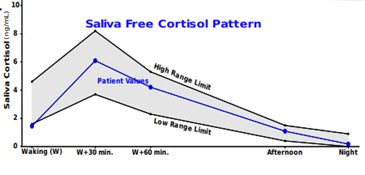

The CAR slingshot can send cortisol sky high. This can happen under a variety of circumstances. Often when the CAR is elevated, waking cortisol is low. This is true in the case below of a 49-year-old female presenting with subclinical hypothyroidism, anxiety, elevated reverse T3 on lab testing, and extreme daytime fatigue.

Waking cortisol low = flattened diurnal slope

CAR = high at 320% rise (NL range 50-160%)

If you evaluated just diurnal cortisol without the CAR, this patient might appear to have an underperforming HPA axis. And the actual hyperreactivity of the HPA would be missed.

Main Causes of an Elevated CAR

These are some of the primary causes of an elevated CAR.

- Internalizing disorders like depression and/or anxiety

- Anticipatory stress and high sympathetic nervous system activity

- HPA adaptive response to low tissue glucose levels (dysglycemia)

- Sleep duration less than five hours, “short sleep,” or adaptive response to shift work

- Essential fatty acid (EFA) deficiency

Other relatively common underlying etiologies of an elevated CAR are conditions which lead to hypometabolism like hypothyroid states, anemia, and eating disorders including anorexia nervosa presentations. And since this patient’s peripheral thyroid hormone activity was hindered (very high rT3), therapies designed to address stress handling, T4 à T3 conversion and thyroid hormone sensitivity may produce the highest yield results to attenuate the CAR and restore daytime energy levels.

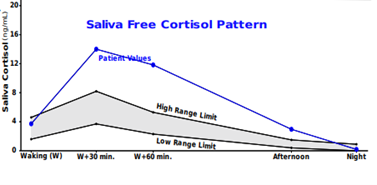

Let’s look at another similar case for consideration. This patient is a 21-year-old male who’s underweight and complains of severe fatigue and depression with difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep.

Waking cortisol normal, afternoon cortisol is high = flattened diurnal slope

CAR = high and prolonged at 270% rise (NL range 50-160%)

His high CAR presentation along with his history of depression and the fact that he’s underweight makes one think about treatments geared toward providing nutrition especially essential fats like docosahexaenoic acid, a good B complex with adequate B5 and B6, and possibly magnesium. If he’s currently untreated for his depression, it’s reasonable to expect that initiating the proper anti-depressant therapy will attenuate the cortisol stress response. Through that mechanism, you can expect improvement in his complaint of fatigue as well.

It’s unlikely one could have gleaned all this from his diurnal pattern alone.

Blunted CAR

What if the CAR slingshot isn’t pulled back far enough during the night of sleep and the rise of cortisol upon awakening is inadequate or even non-existent? A blunted CAR almost always suggests chronicity of dysregulation and even negative effects of stress affecting the brain (regardless of its cause) and resistance to the point of brain-body disconnect.

Common Long-term Chronic Stressors That Present as Fatigue with a Blunted CAR

- Chronic insomnia

- Insulin resistance shifting toward diabetes or diabetic state

- Obstructive sleep apnea

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (chronic)

- Psychological burnout

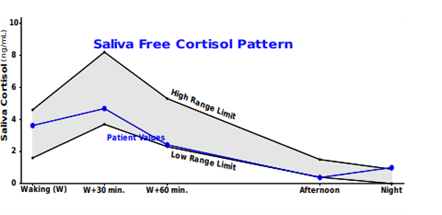

Let’s review the case of a 44-year-old female with the chief complaint of chronic fatigue, who has great difficulty falling asleep, and wakes frequently.

Bedtime cortisol elevated

CAR = blunted 27% rise (NL range 50-160%)

You can see that cortisol rises from evening to night, an odd time for cortisol to rise. This should indicate there are stressors driving cortisol production at the wrong time sending daytime signals at bedtime. For this patient, a focus on the reasons for sleep disturbance would likely be fruitful. Because other causes of blunted CAR are associated with disturbed sleep and circadian disruption, it may make sense to screen for adverse childhood events, PTSD, and even insulin resistance.

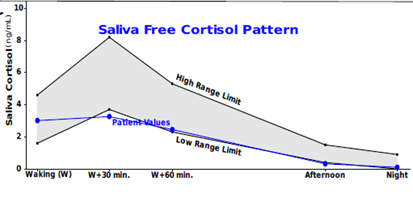

Below is the free cortisol pattern of a 39-year-old male with excessive daytime fatigue that resolves by the evening, depression, anxiety in the mornings, and recent difficulties with memory and recall.

Elevated waking cortisol

CAR = absent (NL range 50-160%)

High waking cortisol alone may suggest an effort to regulate blood/tissue glucose after the long fast of the night. Or perhaps this could be a feature of his depression which at the time of testing was not pharmacologically addressed. The absence of the CAR makes one think his condition is chronic and at this point may be affecting his hippocampal volume given the presence of cognitive changes. One might think about further workup for metabolic issues like insulin and glucose dysregulation, for depression, and consider herbal supports such as Bacopa monnieri and Ginkgo biloba to quell neuro distress in an effort to restore hippocampal function and thus the CAR.

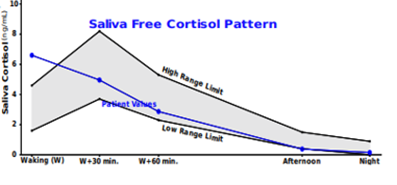

Consider this cortisol pattern in a 45-year-old female patient struggling with morning fatigue.

CAR = blunted 8.7% rise (NL range 50-160%)

Night cortisol (not shown) at 3:00 AM was elevated

Again, without evaluating the CAR, it would be difficult to ascertain the reason for morning fatigue. After all, waking cortisol is perfectly within range. The lack of rise following the waking cortisol sample suggests HPA axis under responsiveness. Efforts to restore glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity centrally with herbal and nutritional adaptogens, optimal sleep, regular, safe, and gentle hormetic stressors like stretching, exercise, and contrast hydrotherapy would be expected to help restore the CAR.

Better HPA Axis Evaluation with DUTCH CAR

Adding the CAR to the functional adrenal assessment can add tremendous value by providing otherwise potentially inaccessible information about HPA axis activity. In fact, it has the power to point the treatment plan in a more specific direction and lead to better outcomes in patients with chronic stress and fatigue.

References

- Abell JG, et al. Recurrent short sleep, chronic insomnia symptoms and salivary cortisol: A 10-year follow-up in the Whitehall II study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;68:91-99.

- Barbalho SM, et al. Ginkgo biloba in the Aging Process: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(3).

- Clow A, et al. The cortisol awakening response: more than a measure of HPA axis function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):97-103.

- Dziurkowska E, et al. Cortisol as a Biomarker of Mental Disorder Severity. J Clin Med. 2021;10(21).

- Ennis GE, et al. The cortisol awakening response and cognition across the adult lifespan. Brain Cogn. 2016;105:66-77.

- Kim EJ, et al. Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review. Learn Mem. 2015;22(9):411-416.

- Labad J, et al. The Role of Sleep Quality, Trait Anxiety and Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Measures in Cognitive Abilities of Healthy Individuals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(20).

- Lopresti AL, et al. Effects of a Bacopa monnieri extract (Bacognize®) on stress, fatigue, quality of life and sleep in adults with self-reported poor sleep: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021;85.

- Stalder T, et al. Assessment of the cortisol awakening response: Expert consensus guidelines. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;63:414-432.

- Thesing CS, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid levels and dysregulations in biological stress systems. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2018;97:206-215.

TAGS

Cortisol Awakening Response

Women's Health

Men's Health